Tuesday, December 29, 2009

A Rough Patch for Treasuries: Much Ado About Nothing?

As attempts at explaining this development have been pouring in, the most commonly offered explanations offered in recent days for the back-up in 10-year Treasury yields by about 60 basis points to the 3.80-3.90% range during that period are mostly zeroing in on the following factors: 1) The prospect that the economic recovery underway may ignite inflationary pressures down the road, 2) The massive budget deficits projected over the next couple of years, in conjunction with the Treasury's expressly stated plan to shift its new issuance toward longer maturities may ultimately cause the market to choke on supply, 3) The easing of the previous anxiety in global financial markets has led to a an increasing gravitation of foreign investors toward emerging markets, therefore abandoning U.S. Treasuries, which in the midst of the financial storm of the last 1 1/2 year had largely played the traditional role of a safe-haven.

Viewed separately, none of the above factors offer a credible explanation as to the timing of the latest sell off in the Treasury market.

First, on the count of inflation fears creeping back into the Treasury market. Hard to believe that such fears are indeed real. The latest round of inflation numbers have been, if anything, reassuring regarding the price picture. Core CPI was flat in November, having averaged 0.1% in the last two months, wage pressures remain non-existent, the labor market slack is at its highest and, by most indications, inflation (given that it is a famously lagging economic indicator) is widely expected to drift somewhat lower over the next 12 to 18 months, even as the economic recovery is taking hold. Moreover, the Fed is already openly, and methodically, positioning itself to start addressing the anxiety-generating issue of its "exit strategy", adopting a posture that can only be assumed to have a soothing effect on the market. To argue that, somehow, against this decidedly benign price backdrop, the Treasury market was abruptly invaded by intense inflation concerns, defies basic facts and stretches any sense of logic.

Second, in regards to the the presumed supply concerns and dismal budget deficit prospects. Sure, but this is nothing new that was suddenly revealed to market participants at the end of November. Forecasts of massive fiscal deficits have been around for nearly a year now and have not become particularly gloomier of late. Moreover, the end of the Fed's program to purchase $300 billion of Treasury securities (which was clearly viewed as a factor supporting the market) had already ended at the end of September (so, nothing new really) and the Treasury had already announced on November 4th its intention to increase its issuance of long-term debt without any immediate adverse reaction visible at the time. In other words, it does not appear that anything new broke on the supply front around the turn of the month that would justify a fairly substantial back-up in long-tern yields.

Third, the story about a steady increase in global investors' risk appetite-resulting into a massive influx of capital in emerging market economies is hardly a new one; it has been a dominant theme for several months now, with only a" manageable", and rather transient, adverse effect on Treasury yields previously.

Perhaps a better framework for interpreting the latest back-up in yields would require a more practical, down-to-earth, approach that takes into account some simple realities as to how markets function, and which often get brushed aside to make room for more rational-sounding "explanations".

To start with, the latest rise in long-term yields, both in terms of the magnitude of the increase and also the absolute levels reached, was nothing particularly unusual to justify the emergence of any new anxiety about the direction of rates. In fact, 10-year yields touched 4% in June- having risen by 150 basis points since early spring- only to drop again to below 3 1/4% by October. The transparent, and understandable, reason for the much sharper back-up earlier in the year was the realization that the economy was about to emerge from the recession and previous assumptions about the potential deflation risk were quickly downgraded. The subsequent realization that the economic recovery was likely to be of the moderate kind, by historical standards, allowed to a pullback in yields by fall.

What is often missing from attempts to explain the Treasury market's every twist and turn is the very realization that markets are notoriously emotional entities. As such, they often have mood swings that can be triggered by any set of factors, which may have been lurking in the background fairly innocuously for a while suddenly come to the forefront, becoming every one's favorite "reason" for a certain price action. While none of the three "explanations" discussed above in this article make sense in isolation, all put together form the semblance of a rational backdrop against which the latest rise in yields can be viewed. It is also crucial to recognize that the latest sell off took place in the midst of mostly thin, holiday trading, undermining its true significance further.

To be sure, with the economy switching into a solid growth pattern ahead and the Fed on standby to start reversing the exceptionally easy monetary policy at some point over the next six to twelve months, Treasury yields are likely to move on balance somewhat higher in 2010. This would be hardly a ground-breaking development worth endless stories with purported "in-depth" explanations as to its underlying reasons. After all, that is what almost always yields do when the business cycle turns. That rise may be quite a circuitous affair. In fact, when the timing of Fed tightening is viewed as within reach, markets, in true form, are likely to overreact and yields may initially rise violently in the context of a flattening yield curve, while such an overreaction may be subsequently tempered by the realization that inflation is likely to remain firmly under control with the Fed in a highly vigilant posture.

But over-analyzing a fairly "run-of-the-mill" rise in Treasury yields over the last several weeks is probably a case of much ado about nothing...

Anthony Karydakis

Monday, December 28, 2009

A Holiday Gift from The Treasury

By Scott Tolep

On Christmas Eve, the US Treasury announced that it would provide unlimited capital over the next three years, if necessary, to cover losses suffered by mortgage agencies Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (previously the limit was set at $200 billion each). The obvious initial reaction here is that the Treasury is issuing a “blank check” to the mortgage agencies and is jeopardizing the future direction and size of the ever-growing public debt. However, there are four compelling reasons to believe that the Treasury’s decision will not increase the public debt and will support the continued stabilization of the housing market and economy:

(1) After December 31, 2009, The Treasury will discontinue its purchases of MBS, which have totaled around $200 billion since the onset of the housing crisis and have kept mortgage rates at historical lows (The Fed has a separate MBS purchase program, set to expire at the end of first quarter 2010, and is expected to reach $1.25 trillion). The Treasury’s and Fed’s purchases have undoubtedly played key roles in keeping mortgage rates low and dramatically improving the housing market. As of October, unsold inventory of both new and existing homes were at their lowest levels in 3 years or more. It appears that the worst of the housing crisis is over, so it is likely that the agencies have already received the bulk of Treasury capital infusions they'll need (~$110 billion).

(2) Psychology plays an important factor in all markets, and the housing market is no exception. Yes, housing and the economy are stabilizing, but this painful cycle is still fresh in the minds (and bank accounts) of investors and lenders. The US will continue to experience periodic setbacks on the heels of this housing-led recession. With the Treasury discontinuing its MBS purchases, market participants are more likely to overreact to these setbacks, with the potential for destabilizing the housing market and economy and sending them back into a tailspin. The Treasury's decision to provide unlimited capital guarantees to the agencies over the next 3 years mitigates this risk.(3) The Treasury has gained significant credibility after recovering a large percentage of the TARP funds it had injected into the banking system. It was announced earlier this month that $185 of the $245 billion that TARP invested in banks (75% of total) is scheduled to be returned to taxpayers with a profit.

http://news.yahoo.com/s/nm/20091215/bs_nm/us_usa_bailout_treasury.(4) The Treasury’s decision should not lead to a loss of market discipline or create a “too-big-to-fail” attitude within the Agencies, as they are both currently under government control and underwriting standards are much tougher than they were in the 2005-2007 era.

Tuesday, December 22, 2009

Taking Advantage of the Low Yields

10-Year Treasury Yield

In announcing that decision, in the context of the quarterly press conference unveiling its broader financing plans, the Treasury went at great lengths to emphasize that the project of lengthening the average maturity of its debt would be implemented very gradually to avoid disrupting market expectations and breaking abruptly with past patterns. Still, a target of reaching an average of 60 months in fiscal 2010 was stated, with an eye on extending it to 84 months over the medium-term, which would represent a historical high.

The Treasury's decision to extend the average maturity of its debt is a sound one, not only on the grounds of prudent borrowing management by spreading out its debt burden over a longer horizon but also on the count of reducing its borrowing costs over time. The latter rationale has generally been a sensitive issue for the Treasury over the years, as it has always maintained that it is not in the business of attempting to "time the market" by adopting views on the future direction of interest rates- an overall sensible approach for a government.

Still, taking advantage, in a measured way, of the unusually low levels of long-term yields (courtesy of a severe financial crisis and associated economic recession) to implement a solid debt management principle of better balancing the ratio of short- to long-term outstanding debt makes perfect sense. Inasmuch as the Treasury wants, understandably, to stay clear of the hazardous enterprise of predicting interest rates, ignoring completely a historical opportunity that would allow it to materially reduce its interest costs on a mushrooming debt over the medium-term would be almost tantamount to malpractice.

Anthony Karydakis

Thursday, December 17, 2009

The Undervalued Yuan: And Then There Was Silence

Tuesday, December 15, 2009

A certain Senator from Connecticut

Sunday, December 13, 2009

As Lending Continues to Shrink...

Thursday, December 10, 2009

A Propos Greece's Troubles

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB126039835690184387.html

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704825504574586410597112166.html

At the core of the attention-getting developments of the last few days is the massive budget deficits and total amount of debt that these countries have accumulated, mostly, but not exclusively, due to the financial crisis and global economic downturn of the last two years. Although, it is actually unlikely that a euro-zone country, like Greece (which is facing the most serious problems) will be allowed by the EU to default on its debt- with Angela Merkel reminding investors as much earlier today-credit default swaps have soared.

A few thoughts.

a) The reassurance offered by the powers-that-be in the euro-system about offering help to its members currently in trouble is obviously a positive development, but it may not be enough to resolve the issue. Greece is already resisting EU pressure to implement any major belt-tightening measures of its own as politically untenable and offers only promises of bringing its budget deficit from 12.7% of GDP this year to about 10% next year. That is likely to be viewed as a frustratingly slow pace to many. Against such obstinacy, it may not be too far down the line, where massive bets against the country's ability to contain its debt burden start being placed by global macro hedge funds- not totally unlike those that were already pushing Iceland (a non-euro zone country) against the wall as the financial crisis was erupting in 2008. (In fact the second of the above links describes exactly those emerging strategies by some). This would represent a major complication for any bail-out efforts by the EU.

2) Directly linked to the above point, the problems that Greece and Spain are facing- and, possibly, Ireland, Italy, and Portugal to various degrees- are not solely the result of the size of their budget deficits per se but more of the lack of credibility that those countries have in the eyes of global investors in terms of their determination to bring them under control. For example, Germany's budget deficit is surpassing 6% of GDP this year but Germany's sovereign debt still carries some of the lowest rates in the euro area and credit default swaps on such debt have not budged. Nobody questions Germany's commitment to reining in the deficit as economic growth picks up into next year. Of course, another key differentiating factor is the total amount of debt of the various countries involved, with Greece's exceeding 125% of its GDP, while other healthier euro-zone economies are only moderately exceeding the 60% cap mandated by the "growth and stability" pact.

3) In a way, the current predicament of the three main countries in trouble currently represents the moment of reckoning for reckless and short-sighted policies earlier in the decade, mostly driven by a goal of creating an aura of unusual prosperity largely built on sand (Ireland, Greece). The financial crisis and associated economic downturn simply helped expose the underlying fault lines of such growth.

4) Finally, it is tempting to highlight that there has been a reversal of past patterns and prevailing stereotypes as to the resiliency that different economies around the world demonstrate in the face of global financial market events of extreme stress. While emerging market economies used to be considered "high-risk" in such situations- and there is admittedly a long history of defaults on their debt to support that perception- it has been exactly those economies that have weathered best the financial turmoil of the last two years. Even Argentina, a serial offender in terms of defaulting on its debt in the last 30 years, is taking positive steps opening up its access to international capital markets again, by announcing today a decision to swap out of $20 billion of defaulted debt.

All in all, another strong reminder, following Dubai's recent problems, that, although the global financial crisis has been by and large successfully contained, pockets of extreme fragility have been left behind and are not likely to disappear any time soon.

Anthony Karydakis

Tuesday, December 8, 2009

No Deflation Ahead

5-year TIPS Break-evens

Source: Bloomberg

10-year TIPS Break-evens

Source: Bloomberg

Simply put, the restoration of these spreads to pre-crisis levels, reflects the belief that the worst of the banking crisis is behind us and that the economy is recovering at a sufficient pace (irrespective of what specific number, or additional qualitative adjective, is attached to it) to ensure the gradual return of inflation to trend. As one would have expected the implied rate of inflation expectations over the 5-year horizon is somewhat lower than the one over the 10-year horizon, as the weight of 2010 (when inflation should remain especially weak) is obviously greater in a 5-year period as opposed to a 10-year one.

Another, fairly closely watched but admittedly "soft", gauge of inflation expectations is the "5- to 10-year inflation expectations" component of the University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Survey, which continues to hover around the 3% mark in recent months. This is somewhat higher than the anticipated rate of inflation reflected in the TIPS break-evens, which is to be expected, as consumers' perception of inflation is typically associated with a higher number than the one officially measured by the CPI. On that score, it is worth recognizing that even the "short-tern inflation expectations" component of the University of Michigan survey (representing a 1-year horizon) is also anchored just below 3%.

Somewhat unscientific as these consumer inflation expectations measures may be, they still corroborate the financial market's fairly more rigorous perceptions of the price outlook and they certainly betray no uneasiness over any prospect of deflation, which, at the margin, could make the latter a self-fulfilling prophecy of sorts.

Deflation, as a trend and not as a short-lived quirk of year-on-year comparison in the various price statistics, is a phenomenon very hard to come by and Japan is the only major industrialized country to have experienced it in recent history- largely as a result of a double meltdown in its stock markets and banking system in the 90s and a notoriously slow policy response to address it. But both of these two potentially extremely destabilizing dynamics seem to have been contained in the U.S. at the present and, as a result, have convincingly pushed the risk of deflation to the sidelines.

Anthony Karydakis

Friday, December 4, 2009

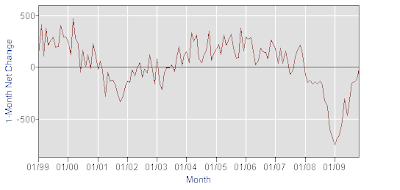

The Employment Picture Brightens Up Suddenly, In a Major Way

It is not only that November's decline in payrolls was a mere 11,000 but, even perhaps even more importantly, there was a massive net cumulative upward revision of 159,000 in the payroll data for the prior two months. The result is a dramatically different profile of recent payroll trends, showing a faster improvement than previously thought. Payroll declines in the last 3 months have averaged 87,000 a month versus average declines of 307,000 in the preceding 3-month period and -491,000 in the 3-month period prior to that.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Adding impetus to the impressive strength of the report- compared to the relatively recent past- the average workweek rose to 33.2 hours from its cycle-low of 33.0 hours. Any moderate sustained rise in the workweek is usually viewed as a precursor of more hiring down the line, as there are limits as to how intensively employers can utilize their existing labor force before adding to it. The manufacturing workweek also jumped by 0.3 hours to 40.4, supporting evidence of a significant turnaround in that sector, as manifested by the ISM and other manufacturing surveys in recent months.

Both construction and manufacturing employment fell last month, by 27,000 and 41,000 respectively, but these are two sectors unlikely to become significant sources of job creation in the foreseeable future, as construction is likely to remain in deep freeze for some time and the bulk of increased output in manufacturing recently comes from a rise in productivity. It is also a sign of the ongoing caution that employers are still exercising in terms of hiring that temporary jobs rose by 57,000 in November and have increased by a total 117,000 since July.

However, all of the still present pockets of weakness in the payroll data need to be understood in the context of the dynamic that prevails around turning points of the cycle- meaning that not all sectors will be showing the same measure of improvement simultaneously and this is likely to be particularly true this time in view of the severity of the last recession and the major dislocations it has caused.

With the pace of layoffs slowing precipitously in the last several weeks, as measured by a strong downtrend in initial unemployment claims, monthly payroll data are poised to start turning positive in the coming months. In fact, the most reasonable expectation at this point is that by early next year, we will start seeing modest to moderate monthly gains, while the unemployment rate may continue to linger around its cycle-highs. But today's report, along with the totality of the other pieces of economic data recently, suggests that the impetus that this economic recovery is having may have been seriously underestimated.

Anthony Karydakis