Let's start with an indisputable fact. The U.S. budget deficit recently reached near-stratospheric levels, representing (at $1.42 trillion in fiscal year 2009), approximately 10% of GDP. This is about 3 times higher the rate that is generally considered as acceptable, or manageable, among the industrialized economies. The natural implication of that is that there needs to be an extremely high degree of awareness about the need for the deficit to come down in the next few years. No sane person would object to any of that so far.

But, judging by opinion polls in the last few months- meant to evaluate the degree of approval that President Obama enjoys with the American public- it appears that one of the main consistent criticisms leveled at his job performance so far is that he is doing a poor job at handling the fiscal situation. That is where things seem to get dangerously off the path of both reality and rationality- no doubt due to a poor understanding by the broader public of the factors that shape the fiscal picture of the country.

To begin with, the new Administration cannot be held responsible for the fiscal 2009 deficit, as this was based on a budget that had already been set by the Bush Administration and the fiscal year was already one third underway when Obama took office in late January.

The reason for the explosion of the budget deficit in the last fiscal year was the combined result of two factors that had nothing to do with the new President: the meltdown of the financial system with its associated bank bailouts and an unusually deep and prolonged recession. The first of the two represents very simply the cost of cleaning up after the banking crisis (which had was already underway some five months before Obama even took office), while the second reflects the massive loss of tax revenue and increase in certain types of government spending that are always associated with an economic downturn and higher unemployment.

So, now we have established -and there is probably very little quarrel with that outside the Fox News Channel's "commentators"- that the Obama Administration did not at least cause the skyrocketing deficit. Let's take a closer look at the repeatedly expressed "concerns" of the American public that the Administration is not doing enough to control the deficits.

There are two types of action that the Administration can take to actively seek the reduction of the deficit: cut spending or increase taxes. Increasing taxes in the midst of a severe recession is simply a catastrophic action, as it would have weakened much further an already plunging pace of consumer spending, therefore throwing the economy into an even more pronounced downward spiral. Cutting spending on programs, like the federally-funded, multiple extensions of unemployment benefits, would not only increase immensely the economic hardship of millions of Americans but would have also, from the strictly macroeconomic standpoint, allowed income growth to suffer more severe damage (which would have contributed to a further deepening of the recession).

One finds it almost irresistible to ask those who state that one of their main concerns about the direction of the country is the administration's poor handling of the fiscal deficit, whether they would have preferred a sharp increase in their taxes and shorter unemployment benefits when they lose their job, so that the new President shows a tougher stance on tackling the deficit. Or, whether, they would have preferred less spending on the various government assistance programs designed to prop up the economy in their own state, like construction projects and the like. When confronted with these options for dealing with the deficit problem more aggressively, perhaps they might (but, then again...they might not) recognize how ill-informed and misguided their criticism of the fiscal situation and those they consider responsible for it is.

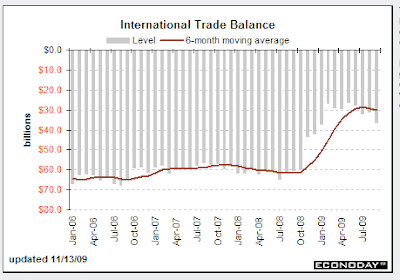

The deficit is bound to come down appreciably in the current fiscal year- perhaps close to $1 trillion- as a direct result of the improvement in economic activity and the ensuing pick up in tax revenues. Left to its own devices, it should continue to move lower in fiscal year 2011, as the economic recovery gathers momentum. This is the way things always work with regard to the part of the budget deficit that has been affected by the down phase of the business cycle ("cyclical deficit").

In fiscal 2010, in particular, there is still a moderate headwind toward any further shrinking of the deficit coming from the remainder of the fiscal stimulus package coming on line, but ultimately, the deficit will be trending lower in the next few years. Whether such a downtrend will come soon enough on its own to return it to the 3.0% range by 2013, as Obama has promised, or whether more "pro-active" steps will be needed, that remains to be seen. For the time being, though, as Tim Geithner sensibly put it in an interview today (link below)

the deficit can wait, as the undiluted emphasis should remain on securing that the emerging economic recovery will acquire a self-sustaining dynamic soon.

Anthony Karydakis